Trump & Greenland: Is There Logic in the Chaos?

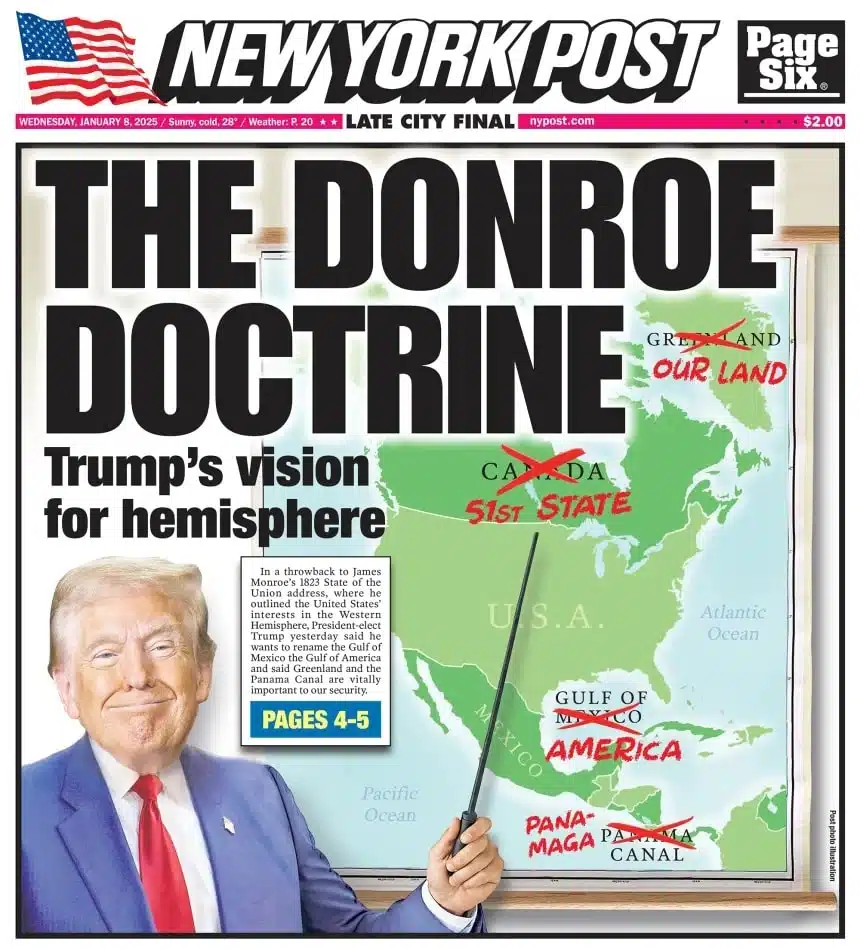

Frontpage of the New York Post on January 6, 2025, showing an altered image where Trump highlights the nearby states to the United States. Photo: New York Post (via CNN)

Why does Trump still want to take control of Greenland? What could happen in 2026 and what concessions might Denmark have to give?

The saga of Trump’s obsession with Greenland will never end. Let’s try to clear up a little bit of what’s behind it.

Argument 1: Greenland has huge untapped mineral resources on land that the US needs

Greenland has large proven resources and even several mines that are already extracting minerals. As we see in both the discussions around Ukraine and Venezuela, Trump is clearly driven by a desire for economic gain by giving American companies special access to deals and opportunities. Perhaps this explains Trump’s interest in Greenland. It is also rumored that it was an Australian geologist who in 2019 made Trump aware of the resource potential there.

But is this enough to justify a possible break with European allies and the collapse of NATO? Doubtful. The US does not need to have sovereignty over Greenland to access resources. Nor is it “the US” that extracts resources, it is companies. There are other parts of the Arctic, such as Alaska, that have great untapped mineral potential.

If these logical arguments do not convince Trump, perhaps a further release of areas for mining – possibly in conflict with Greenlandic interests – and prioritizing American companies in cooperation with Greenlandic ones would be a possible solution? This would violate competition rules and not least the right of the Greenlandic people to decide for themselves what and how to extract their own resources. But perhaps this is a concession Denmark and Greenland have to accept to satisfy the US.

Argument 2: The US needs control over Greenland to stop Russian and Chinese ships that are “all over the place“

Here Trump literally misses the mark. The Arctic is a huge area that makes up four percent of the globe and includes the Arctic Ocean, which itself is six times larger than the Mediterranean Sea. Parts of the Arctic are absolutely central to Russia’s strategic nuclear weapons, i.e. Russia’s ability to threaten the West and especially the United States with nuclear war. These weapons in the form of missiles, bombs and warheads on submarines are mostly located on the Kola Peninsula – a stone’s throw away from Kirkenes and Norway – not Greenland.

There, Russia can operate relatively freely, protected by ice, cold, and geography. It is also where the shortest direct route as the crow flies is from anywhere in Russia to key targets along the East Coast of the United States. This puts Greenland right in the firing line, even though the missiles and bombers mainly fly over Greenland on their way to Washington, D.C. That’s why the US already has a military base, the Pituffik base, on the northwest side of the island, where the US Space Force monitors anything that might come flying from Russia.

Do Russian naval vessels, however, sail around Greenland? No. They sail in the Barents Sea around Svalbard and along the Norwegian coast to show that they can stop any attacks on the nuclear weapons on the Kola Peninsula. There may be some Russian submarines sailing around Greenland, but hardly more there than around the Canadian islands in the north or around Iceland a little further south.

What about China? China is obviously interested in the “Arctic”, they even have their own Arctic policy from 2018. But China does not have its own territory in the region, and it is far from Beijing to the Arctic Circle. First and foremost, China is interested in using the Arctic as an arena to project power and at the same time earn a few yuan, interspersed with strategic positioning in anticipation of further melting of the ice.

Do Chinese ships sail around Greenland? No. They mainly sail to and from Russia with raw materials, and they sail outside Alaska to hold military exercises, to conduct research, and to fish. Yes, China (or, to be more precise, Chinese companies) has been interested in investing in Greenland, especially in mining. But many of those projects have been put on hold for security reasons.

The conclusion is thus: if Trump is concerned about Russia’s dominance in the Arctic, he should focus on what Russia is doing in Northern Europe from Estonia to Svalbard, or what Russia is doing together with China outside Alaska. At the same time, he cannot possibly be that worried about Russia in the Arctic, since he has repeatedly hinted that the United States and Russia should enter into major economic cooperation projects in the Arctic. This was also the topic when Trump met Putin in Alaska, in August 2025. (which subsequently led to the reemergence of the utopian idea of a “Putin-Trump tunnel” between the continents).

If it’s China that keeps him up at night, the focus should be on Alaska and what China is increasingly doing there. Not least, he should think a little about how America’s global standing, power, and influence are declining as countries can no longer rely on the United States in everything from trade to international agreements.

But it is not inconceivable that Denmark will have to give into some expensive concessions here too to deal with Trump’s concerns. The government in Copenhagen has already promised to invest over 6 billion USD in various defense capabilities in Greenland. Denmark will buy both more F-35 fighter jets and P-8 surveillance aircraft from the United States to deal with any threats in the Arctic. This will, however, probably not be enough.

Maybe a new Danish and/or American base needs to be built on the island? Maybe a symbolic defense agreement needs to be put in place, where the US officially becomes responsible for the defense of Greenland? Maybe Denmark needs to send its frigates and fighter jets to Alaska to contribute to exercises in that part of the Arctic to show that they are a valuable Arctic ally for Trump’s USA? Symbolic acts and achieving a “good deal” obviously weigh heavily on the incumbent US president.

Argument 3: Control over Greenland is about the “Donroe doctrine” and Trump’s desire for dominance in the near-abroad

This is the most frightening scenario that also entails the greatest threats for the Kingdom of Denmark (and other Arctic “allies”). Trump’s press conference on January 4 was a clear signal of what he has in mind. With a smile, he referred to the Monroe Doctrine (after President James Monroe in 1823) which is about other countries not interfering in the American continent (both North and South). It is obvious that a variant of this has become an inspiration for the security policy of the Trump administration.

American control over Panama, Cuba, Venezuela and Greenland is part of this picture. The argument is that the US should decide what happens in its immediate vicinity, in the same way that Russia wants to control what happens in Estonia, Ukraine and Moldova, and China in Vietnam, Mongolia and Taiwan. This is 19th century great power politics: the most powerful gets to rule in its immediate vicinity, and international rules are primarily about limiting other great powers, not about protecting universal principles or the sovereignty of small states.

If this “doctrine” and approach to international politics is the guideline for the United States, it is bad news for the Kingdom of Denmark. In such a perspective, it is not unnatural that the United States has some form of “control” over Greenland and determines what happens on the world’s largest island. In such a perspective, it is also not unnatural for Russia, for example, to think that the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard – due to its strategic location and proximity to the Kola Peninsula – should be Russian, or at least a joint ownership between Norway and Russia, as the Soviet Union already proposed in 1944.

The problem for Trump is that the world has largely evolved away from this mindset, which, among other things, paved the way for World War I. In contrast to a zero-sum game where the other side’s success is your defeat, today’s international policy makers believe that by respecting each other’s borders and agreeing on common rules linked to everything from trade to sovereignty, we will all benefit in the long run.

These are the principles that European leaders are safeguarding when responding to Trump’s comments about Greenland. But if Trump wants to pursue his “Donroe Doctrine” to the fullest extent, neither rebuttals, nor mineral and defense deals, will be enough to satisfy his desire for power and control.

At the same time, it is still unlikely that the United States will use military force against Denmark. Denmark is not Venezuela. The moment the United States uses military force, the NATO alliance is history, the transatlantic security guarantee is dead, and many European countries will find themselves in their greatest security crisis since World War II.

Trump understands this too. In addition, his generals and admirals understand this, and they are aware that such an action would have to be approved by Congress. Trump cannot do this alone. Therefore, it is doubtful that such an action would even be possible.

What Trump can do, however, is to push for some form of “deal” that fulfills the intention of control through upholding pressure on Greenland and the Kingdom of Denmark by for example increasing American military activity in and around Greenland, continue to interfere in local politics, and come with additional public announcements and threats.

A possible solution for Denmark in the face of such a scenario would be to accelerate the already ongoing independence process in Greenland. A report is expected from the Greenlandic self-government by the end of 2026 that will point out possible alternatives for independence. The majority of Greenlanders want independence from Denmark, but only when it is economically feasible.

A referendum on an independent Greenland with a subsequent result leading to a new state could silence Trump’s rhetoric. Especially if the new country is part of a security policy umbrella with the US and Canada (which it de-facto already is). But in such a scenario, the US would also have to cover the costs.

The concession of independence will probably be the hardest for any government in Copenhagen to accept. The Kingdom would then lose its status as an Arctic country and its special role across the North Atlantic. Denmark’s Mette Frederiksen is unlikely to want to be remembered as the prime minister who lost half the kingdom (or 98 percent, measured in land area).

The immediate response from both Mette Frederiksen and other European leaders in 2026 has been to stand up to the schoolyard bully. That could be effective, especially if the goal is to hold out until Trump faces a possible defeat in the November midterm elections. The alternative is to start looking for the lesser of painful concessions that might placate Trump.

This article was originally published by the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten – in Norwegian – on 7 January 2026.

Andreas Østhagen is the Research Director Oceans and the Arctic at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute & Senior Advisor at the High North Center at Nord University, as well as a Senior Fellow at The Arctic Institute.