Digital Arcticism? Exploring Arctic Connotations on Facebook

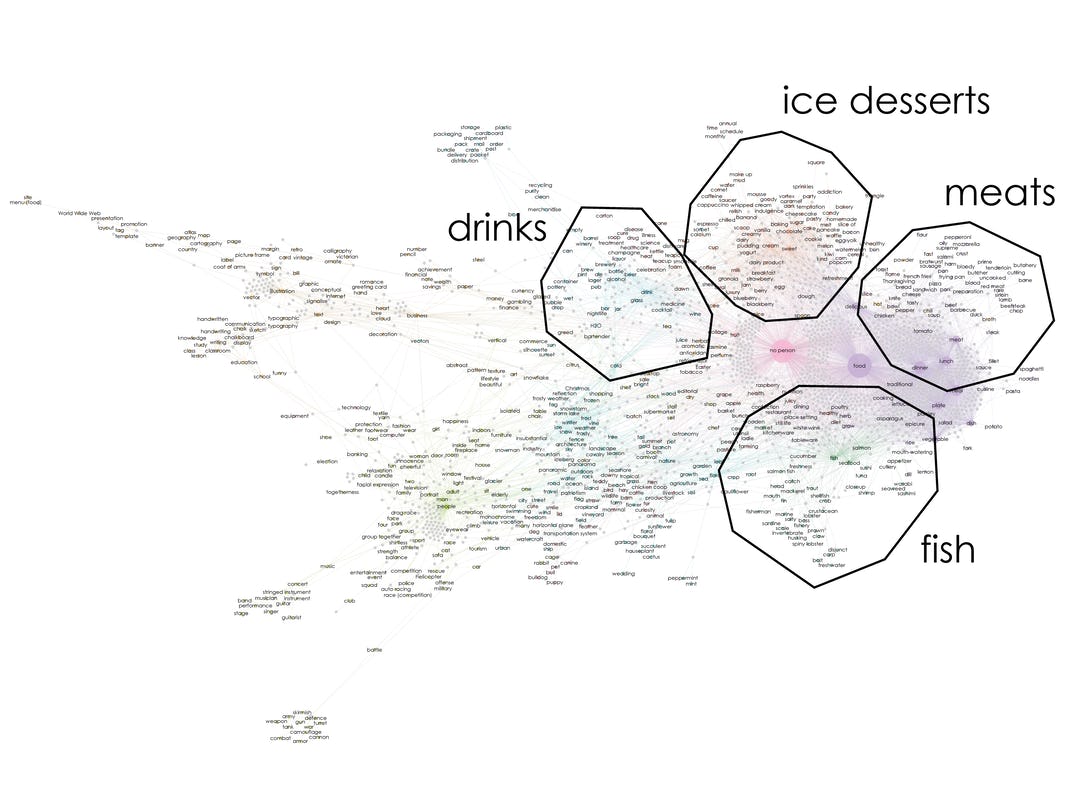

What happens if we let an algorithm predict topics in culinary images associated with the Arctic? For a higher resolution image of the figure, please see here. Photo: Anders Kristian Munk

Much research on Arctic imaginaries has criticized how explorers, missionaries, and artists from the South have, in past centuries, envisioned and portrayed the Arctic in exotifying ways. In line with Said’s concept of orientalism (1978), Ryall et al. have described how such discourses have shaped the interplay between expectation and experience, labelling this phenomenon ‘Arcticism’.1)

Recently, in a satirical article, Heather Exner-Pirot urged first-time Arctic reporters to draw on recurrent media tropes such as, among others, climate change, Arctic conflict, frozen landscapes, and ‘trillion dollar’ resource potentials in their work to ensure publication success,2) thus pointing to how exotification and dramatic headlines continue to linger in journalistic accounts of the region.

Arguably, our social imagination is increasingly fueled by our interactions online, not least on social media. Yet, few studies have explicitly dealt with how the Arctic is represented on these media platforms beyond, perhaps, the confines of Arctic specific sites.3) In order to build our understanding of how current representations of the Arctic are (re)produced or challenged online, this article explores visual traces of the Arctic in food-related social media talk.

By analyzing images from food and gastronomy pages on Facebook, we are able to identify recurrent visual themes in posts that reference something ‘arctic’. Facebook was chosen for the experiment since a) it has high penetration in most countries, b) it is widely used in gastronomic contexts, much like Instagram, and c) it provides an operable way of crawling a large global corpus of food related public pages, unlike Instagram. We chose a single query term because we needed a stable reference point for the subsequent comparison of visual themes. We chose the term ‘arctic’ as we judged it to be more specific than terms like ‘northern’, yet with more room for diverse connotations than terms like ‘Inuit’ (which was very sparsely represented in our dataset).

As we will show, we take these visual themes to be a data-driven indicator (in the sense that the themes emerge by asking an algorithm to predict topics in the images) of how food actors around the globe make use of the Arctic – metaphorically or literally – as a reference point in their social media activity. By exploring this dynamic, we get a partial view into how the Arctic is connoted, in the sense of being associated with certain themes, in the ongoing worldwide food conversation on social media. Similarly to fashion, music, or film, exploring food connotations offers a detailed view into largely under-explored imaginaries of the Arctic’s globally growing cultural and creative industries.

How did we do it?

For our analysis of Arctic connotations on Facebook, we draw on a corpus of 102,000,000 posts from 250,000 public pages on Facebook related to food and gastronomy. The corpus was harvested through the open Graph API (Application Programming Interface, which allows third parties access to selected endpoints in the Facebook database) during Spring 2018 in a four-step snowballing process:

- We compiled a seed list of food related Facebook pages, typically international restaurant magazines like Fine Dining Lovers or The World’s 50 Best Restaurants. The seed deliberately consisted of mainstream, global, culinary media pages since the corpus we were aiming to build should represent the global, culinary discourse. The seed pages then pointed our crawler to more pages.

- We asked the Facebook Graph API which other pages were ‘liked’ by each page on our seed list. We also asked the API to tell us which page categories these ‘liked’ pages were listed under. At the point of harvest, owners of a Facebook page could decide between 1544 different categories and were not restricted to listing their page under one category only. A page may therefore both be an ‘Italian Restaurant’ and a ‘Wine Bar’, or a ‘Chef’ and a ‘Public Figure’. If a page was listed under a food related category, we included it in the corpus.

- When we were done checking all the pages on the seed list for page ‘likes’, we repeated the process on the next layer of newly added pages in the corpus. We iterated this step until we reached 250,000 pages.

- For each page in the corpus, we asked the Facebook Graph API to return a list of all posts authored by this page. In some cases, this step returned posts as far back as 2010.

From this corpus, we selected all the posts that contained an image and mentioned the word ‘arctic’ in the post message accompanying the image. This filtering produced a subset of 9,800 posts from 5,500 pages.

In our analysis, we took these images to be potential representations of the Arctic. It is of course an open question in what way this may or may not be the case. An image may be shared with an accompanying text mentioning something ‘arctic’ by a food related Facebook page for a variety of reasons. Our analysis mapped this variety of representational forms in two steps:

- We used an image tagger to predict the contents of each image in the dataset. For each image, we retained only the content tags predicted with a 95% confidence interval or higher. Even with this threshold, each image typically retained more than one content tag, for example ‘fish’, ‘seafood’, and ‘salmon’. This allowed us to build an undirected bi-partial network of images and content tags. An image may be connected to several tags and a tag may be connected to several images in this graph, but an image can never be directly connected to other images, just like a tag can never be connected to other tags.

- Next, we used a community detection algorithm to divide the graph into clusters (specifically the Louvain modularity, a method which attempts to carve the network into smaller sections with minimal loss of edges). Each cluster represented a ‘community’ of images and tags that tend to be more intensely connected to each other than they are to other tags and images in the graph. We can interpret such a community as a set of images that tend to be tagged with the same content by the model.

In the Facebook corpus visible below [figure 1], we can identify four distinct clusters, around which the Arctic was particularly present. These were fish, ice desserts, meats, and drinks.

Arctic char, cold meat, and Alaska bakes

The fish cluster mainly consists of images of Arctic char, a cold-water fish closely related to salmon. The Arctic char is native to alpine lakes, and Arctic and subarctic coastal waters. In the image cluster, it is typically depicted raw, either whole or filleted, sometimes alongside other seafood.

The ice dessert cluster consists of images where ice cream is a main ingredient in a dish, typically in a dessert with fruits and/or baked into meringue in some form or another (e.g. Alaska bakes and other frozen delights).

The meat cluster consists of images of either fresh cuts or cooked pieces of meat and sausages. These images are often posted by meat retailers that brand themselves with the word ‘arctic’, presumably to connote cold storage.

Finally, the drinks cluster consists of images of beers and cocktails that include ‘arctic’ in their name.

Along with these four cluster are a number of less obvious (lower density) clusters with no robust visual theme. Images in these clusters are loosely connected by the fact that they – as opposed to most of the images in the corpus – have people in them, for example, or that they depict outdoor scenes.

Digital Arcticism?

While the usual Arctic connotations of climate change concerns, conflict, or landscapes open for exploration were distinctively and unsurprisingly missing in this gastronomy corpus, much of the imagery emerging in the corpus and cluster of this vast digital material is very far from other stereotypical and everyday representations of the Arctic. We neither have vast, empty, and frozen landscapes, nor mundane snapshots from daily life above the Arctic Circle. Yet, references to “the frozen” and “the fresh” lingered in some of the images or accompanying text for aesthetic or discursive references. Apart from the few very loosely connected posts that were mentioned, references to or representations of everyday life in the Arctic or of Arctic inhabitants were also lacking in this corpus.

Some food actors use what some might term as cultural appropriation in connoting their products with Arctic characteristics. Predominantly, global gastronomy actors on Facebook deployed stereotypical Arctic features such as cold (ice, drinks) and freshness (fish, meat). Similarly to critiques of Southern cultural (mis)representations of the Arctic in social media,4) the vast majority of the Facebook posts in this gastronomy corpus did not give a voice to local representations of the Arctic. Essentially, local (Arctic) representations of the Arctic did not travel into the global gastro-talk about things ‘Arctic,’ but was replaced with Southern understandings. This indicates that the Arctic imagery in the social media corpus is simply ‘misconnoting’ the Arctic, leading to what we might call “digital Arcticism.”

Activating Arctic connotations in gastronomic entrepreneurship

While such an argument is surely relevant, we could also use our insights to proactively define and develop new Arctic representations of food. In our investigation, we did not look into how Southern connotations differed from those produced by locals in the Arctic. An initial further step would thus be to probe whether and how imagery produced locally in the Arctic differs from that produced elsewhere. This could give us a preliminary indication of what a local Arctic food conversation could look like, informing Arctic and perhaps also Indigenous food politics and digital interventions to reshape gastronomic imaginaries.

Another way to use these findings is to ask how the global imageries and cultural references displayed in this social media network analysis could become relevant for Arctic food and gastronomy entrepreneurs. The digital insights could be activated, for instance, by (re)valuing Indigenous and locally sourced foods and by furthering Arctic products on a home and global market through linking to, but also challenging what we have identified as recognizable and desirable Arctic connotations of coolness and freshness. Such globally food-related imaginaries of the Arctic could also be used to support the Arctic as a food producing region, local food clusters, and further explore the potential of developing and marketing Arctic destinations through their gastronomic qualities.5)

Regardless of whether we see Arctic connotations in food posts on Facebook as digital Arcticism or seeds for developing place-based food products, digital methods such as the ones deployed in this analysis offer promising ways to explore social media conversations on, in, and with the Arctic. As mentioned elsewhere,6) this will require a more just and even access to digital connectivity in the Arctic in the years to come.

Carina Ren is Associate Professor in Tourism and Cultural Innovation and affiliated with The Centre for Innovation and Research in Culture and Living in the Arctic (CIRCLA) at Aalborg University, Denmark. Anders Kristian Munk is Associate Professor in Techno-Anthropology and director of the Techno-Anthropology Lab at Aalborg University in Copenhagen, Denmark.

References