Sustainability Understandings of Arctic Shipping

The German research vessel Polarstern during an expedition into the central Arctic Ocean. Photo: Mario Hoppmann

This is a condensed version of the article ‘Sustainability Understandings of Arctic Shipping’, recently published in the anthology The Politics of Sustainability in the Arctic: Reconfiguring Identity, Time and Space.

The book sets out a theoretical framework for understanding and analysing sustainability as a political concept, and provides a comprehensive empirical investigation of Arctic sustainability discourses. Presenting a range of case studies from a number of Arctic countries including Greenland, Norway and Canada, the essays in this volume analyse the concept of sustainability and how actors are employing and contesting this concept in specific regions within the Arctic. In doing so, the book demonstrates how sustainability is being given new meanings in the postcolonial Arctic and what the political implications are for postcoloniality, nature, and development more broadly. Beyond those interested in the Arctic, this book will also be of great value to students and scholars of sustainability, sustainable development, identity and environmental politics.

The Arctic Institute Sustainability in the Arctic Series 2018

- Sustainability as a Political Concept in the Arctic (Part I)

- Sustainability as a Political Concept in the Arctic (Part II)

- Sustainability Understandings of Arctic Shipping

- Breaking Free: Alaska’s Path Forward for Renewable Arctic Energy

- Sustainable Arctic Mining? A Comparative Analysis of Greenland and Nunavut Mining Discourses

Sustainability Understandings of Arctic Shipping

While the downward trend in Arctic sea ice has thus far not let to a “boom” in commercial Arctic transit shipping, ship numbers and sailing hours in the Arctic are on the rise because of the increase in regional shipping activities. Especially on parts of the Northern Sea Route more ship movements have occurred over recent years due to Russia’s energy development projects along its Arctic coast.

So Arctic shipping activities are happening and will probably increase in the future (predominantly for regional shipping activities), and thus the question of its sustainable conduct arises. What sustainable Arctic shipping is in concrete terms, or how Arctic shipping could be rendered sustainable, is currently not discussed explicitly, neither politically nor academically. Stakeholders seem to agree, however, that Arctic shipping per se is not unsustainable, in the sense that ships should not go through Arctic waters at all. While some actors issue reservations about Arctic shipping, for example in relation to using heavy fuel oil or by calling for prohibiting shipping in particularly sensitive marine areas, there seems to be agreement that shipping can be done sustainably.

This work analyses how different actor groups involved in Arctic shipping conceptualise sustainability in their arguments and storylines. Concretely, sustainability understandings of Arctic shipping are unravelled by showing, first, what it is in concrete terms that should be sustained or developed to be sustained in Arctic shipping and, second, for what purpose.

The analysis includes actors from different groups on various scales (states, NGOs, local communities, industry) as well as actors who have an explicit strategy or policy towards Arctic shipping generally and Northeastern routes specifically. Concretely, this encompasses the Arctic states Norway and Russia; the non-Arctic countries China, Japan, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; the WWF and the Clean Arctic Alliance. All these actors are engaged in the International Maritime Organization (IMO), either as members or with a consultative status, and are thus expected to show a significant interest in shipping issues. To include local actors, the analysis looks at strategies that represent inhabitants and indigenous peoples living in the Arctic as well as business actors operating on Northeastern routes, namely Sovcomflot, Murmansk Shipping Company, and Nordic Bulk Carriers.

Beyond environmental protection and human safety

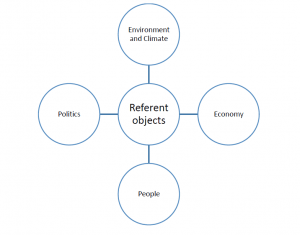

The adoption of the International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters, or Polar Code, highlighted the role of humans on board the ships and the polar marine environment as important referent objects of sustainable shipping. Going beyond the Polar Code and scrutinizing the strategies of various actor groups as outlined above leads to the detection of many more sustainability understandings in relation to Arctic shipping, ranging from living standard and social well-being, health and cultural integrity to economic benefit, political stability/cooperation/peace, national security, and political influence. This provides a rather large array of referent objects of sustainable Arctic shipping, which can be broadly clustered into four categories: Environment and Climate, Economy, People, and Politics (see figure). These four categories are not always clear-cut, since referent objects that are in separate categories are often combined in actors’ strategy documents.

Environment and Climate

With the exception of Russia, all actors mention referent objects in relation to the environment and climate, mostly referring to marine and coastal environments but also to Arctic and global climates. For example:

- Dutch and UK Arctic policy documents support the creation of marine protected areas in the North Pole region to safeguard sensitive areas from shipping impacts and to reduce emissions from shipping;

- WWF mentions the more specific aim to establish particularly sensitive sea areas (PSSAs) under the IMO in the Arctic, and to implement measures to minimise the risk of invasive species;

- Norway strives to improve the safety and efficiency of its maritime activities to protect marine and coastal environments through improved map coverage and satellite data usage;

- WWF and the Clean Arctic Alliance aim to secure a legally binding phase-out of the use and carriage of heavy fuel oil as ship fuel in Arctic waters by 2020 to protect Arctic environments and the climate through ship emission reductions.

Economy

Referent objects related to the economy are the second-biggest group after environment and climate, and feature prominently especially in almost all actors’ shipping strategies. The referent object most frequently mentioned is the national economy, followed by local and international economies, and companies’ market position. For example:

- For Norway, Arctic shipping is deemed important for fostering high economic growth rates for the national economy;

- Russian Arctic shipping is part of the overarching goal of using the Russian Arctic as the country’s “strategic resource base” and to bring Russian hydrocarbons to world markets;

- China hopes to use to the Northern Sea Route to help satisfy Chinese’s demands for resource imports and to support China’s export activities;

- Shipping companies highlight economic benefit for national and international economies through Arctic shipping in combination with improving the respective company’s market position.

People

Frequently mentioned are also humans on board the ships as well as local and coastal communities as referent objects of sustainable Arctic shipping. Surprisingly, indigenous peoples are rather seldom referred to in actors’ shipping strategies. For example:

- Norway and Russia emphasise the importance of adequate training of officers and crew and measures for safe navigation on the Northern Sea Route;

- WWF stresses the importance of maximising the benefits of development for northern people who rely on healthy Arctic ecosystems through equipping ships with the best information, best practices, and the latest technology to avoid or minimise the disruption of wildlife, the introduction of invasive species, and the release of pollutants;

- The 2009 Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment Report (AMSA) report looks into the concerns of local and indigenous peoples as regards Arctic shipping, for example that the continuation of indigenous ways of life and indigenous peoples’ right of self-determination need to be sustained;

- The Russian strategy aims to improve the quality of life of the Russian indigenous population in the Russian Arctic through modernisation and infrastructure development of the Arctic transport system, including shipping.

Politics

More implicitly, one also finds referent objects to be sustained by Arctic shipping in relation to regional and international state relations, countries’ and companies’ strategic positions, and political reputation or standing. For example:

- Norway and Russia mention the relevance of shipping in their efforts to foster regional and international cooperation and the possibility to preserve the Arctic as a zone of peace through the effective use of the Northern Sea Route for international shipping;

- China is hoping to establish and sustain the recognition of the Arctic as an international or inter-regional issue through the increased international usage of the Northern Sea Route;

- Arctic shipping is for China also a means to be respected as a major power and responsible member of the international community.

Discussion

Although actors’ strategies span a wide range of referent objects as outlined above, the analysis found a particularly strong focus on economic notions. Even more, also environmental protection and human safety concerns are often either used in conjunction with economic benefit notions or even employed to achieve the ultimate goal of economic profits. This does not seem too surprising at first sight since shipping is predominantly an activity undertaken for economic ends. But it is nevertheless perpetuating the dominant discourse of valuing the Arctic predominantly from a cost-benefit point of view, which is often regarded as the underlying cause of unsustainable development.

A second interesting observation is that the underlying assumption behind both national and international decisions regarding Arctic shipping in recent years has been that Arctic shipping should or will be enhanced. Put differently, sustainable Arctic shipping seems to mean sustained shipping. Even actors that issue concerns about Arctic shipping assume that it will increasingly take place. Their approach is to influence the legal and technical conditions of Arctic shipping so as to bring it in line with a respective understanding of sustainability. So the approach is not to try to prevent Arctic shipping because of its possible unsustainable features. Ultimately, calls by environmental NGOs for environmental safeguards, such as a ban on heavy fuel oil, are calls for Arctic shipping to take place and to continue (if certain conditions are complied with). This is rather surprising given the many obstacles that large-scale Arctic shipping is still facing today and that it is still doubtful if large-scale Arctic shipping is sustainable even from an economic point of view.

In sum, the Arctic shipping discourse reveals a general notion of allowing, enabling, and enhancing shipping in the Arctic. While actors agree on the principal possibility that Arctic shipping can be sustainable, conflicts arise when considering the concrete referent objects that are to be sustained or developed, and the conditions under which sustainable Arctic shipping can be achieved. To name but one example, environmental NGOs depict the current use of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic as unsustainable, given the tremendous risk it poses to the local environment, communities, and climate. In contrast, shipping operators with a strong focus on economic benefit and the market position of their company speak out in favour of using the relatively cheap heavy fuel oil in order not to render the already cost-intensive Arctic shipping business unsustainable.