China and the Arctic: Reflections in 2023

Pavel Devyatkin and some of the students and professors of the Polar and Ocean Portal at the Ocean University of China in Qingdao in 2023. Photo: Pavel Devyatkin

Is there really a Russian-Chinese partnership in the Arctic? What is China’s role in the Arctic and how far does it go beyond climate change and environmental protection? These are some of the most hotly debated questions in Arctic security studies and they were at the top of my mind when I traveled to China for the first time. This article presents a personal reflection after my work trip as well as a discussion of Chinese positions in and on the Arctic.

In September 2023, I had the great honor to be invited to give lectures on Arctic security and policy to a group of Chinese students and professors at the Ocean University of China in Qingdao, a beautiful seaside city with a rich history of maritime research, the best seafood I have ever had, world famous beer, China’s oldest aquarium, and the headquarters of China’s North Sea Fleet. Ocean University of China is home to the Polar and Ocean Portal, a team of Chinese scholars studying and writing about polar affairs. The team is led by the charismatic Professor Guo Peiqing, who writes about the Chinese perspective on the Nordic countries, together with Chen Huiwen. The group of scholars are incredibly well informed and well connected; the professors consult Chinese Arctic officials and annually organize a research exchange between Chinese and Russian Arctic scholars as part of the Sino-Russian Arctic Forum.

At the Ocean University, I had the pleasure to meet Professor Dong Limin, who first called China a “near-Arctic state,” even though his senior colleagues prefer calling China an “Arctic stakeholder.” In China’s official Arctic policy, Beijing declares it will “work with all other countries to build a community with a shared future for mankind in the Arctic region.”

Sitting in China, the Arctic feels like a distant and romanticized destination. The Arctic Circle is almost 1500 kilometers away from China. At the same time, the Arctic is intimately linked to China’s economy, society, and role in the world. Even in the scorching 33-degree September weather, the Far North felt not too far away as researchers and scholars in Qingdao study the region from all angles, daydream of the northern lights, and eagerly make plans to get involved in Arctic expeditions (almost exclusively to the Russian Arctic zone).

As an American scholar based in Moscow during a period of turbulent political tensions, one of my favorite questions to ask Russians of all walks of life is their attitude towards their country’s relationship with China. The strength or mere existence of a Russian-Chinese partnership is an oft discussed question in policy and academic circles. In general, Russians view China positively and as a reliable partner. 85 percent of Russians polled in August 2023 view China positively. This is especially true of my friends and colleagues in academia. Some scholars scoff at the warning that Russia is bound to be a junior partner to China; one Russian colleague joked with me: “If Russia is supposed to become a junior partner like Canada is to the United States, I don’t see the problem. Who wouldn’t want to live in a place like Canada?” In general, the views expressed in this paper are purely anecdotal.

Many Russians admire China and praise Chinese support for Russia after relations collapsed with the West. They also express skepticism about the temporality of China’s business interests, are averse to the supposedly “exotic and unappetizing cuisine,” and maintain that Russia is more European than Eurasian. In general, there is an acknowledgement that Russia’s future will be tied to that of China. Tellingly, you can observe the business attitudes between the countries when traveling. In Moscow airports, signs and guidelines are all written in Russian, English, and Chinese (and rarely in Central Asian languages). In Chinese airports, there is almost nothing written in Russian. When I first touched down in China and had not yet managed to get my WeChat QR code payment app to work, I offered to pay in foreign cash at a Dim Sum restaurant. The waiters laughed at the rubles in my wallet and said I could pay in euros or dollars. At the same time, the Chinese yuan is the most traded currency in Russia.

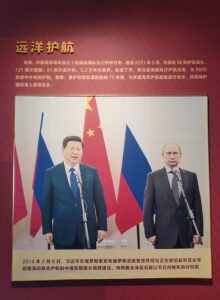

I also enjoyed posing a similar question to my Chinese interlocutors: What is your attitude towards Russia, in the world and in the Arctic? A 2022 poll similarly showed 80 percent of Chinese people view Russia positively. China especially has a positive attitude towards Russia in the wake of the war in Ukraine; Chinese social and news media portray the conflict as Russia’s logical response to United States and NATO policies. I felt this attitude to ring true when I spoke with friends and colleagues in China. Students pointed to NATO’s eastward expansion as a key factor in Vladimir Putin’s decision to send troops into Ukraine in February 2022. Students were happy to share Russian military memes with me, praising the Russian armed forces and the Wagner Group and deriding the Ukrainian armed forces, dubbed in Chinese and distributed across Chinese social media like WeChat, Weibo, Bilibili, and Douyin (TikTok). In general, there is high praise for the military strength and leadership of Russia.

When it comes to the Arctic, the incredibly astute Chinese students connected the region to vast opportunities related to natural resources; Siberia was specifically dubbed a treasure-trove of minerals important wind and solar energy as well as battery production. Wang Yue of Tampere University and the Arctic Centre, University of Lapland will write about the role of the Arctic for China’s energy transition. After my lectures, students asked me questions about the role of the BRICS in Arctic development and whether the impasse in the Arctic Council warranted a new Arctic institution for the BRICS countries. Russia, India, and China have long been involved in Arctic affairs and seek to establish a joint research station on Svalbard, while new BRICS members such as the United Arab Emirates are slowly entering the market of Arctic infrastructure development. There were also questions about how the Shanghai Cooperation Organization could play a role in the Arctic. The students were attentive to the activities of the SCO; Qingdao hosted China’s previous SCO Heads of State summit in 2018. The slogans of the SCO – Mutual Trust and Benefit, Win-Win Cooperation – are likewise declared in China’s 2018 Arctic policy.

The theme of China’s neutrality was emphasized throughout my discussions with Chinese scholars. China has officially been a neutral party in the Ukraine conflict. Karoliina Hurri of the Arctic Centre, University of Lapland and TAI’s Sanna Kopra will write about how this has affected the implementation of China’s climate policy in the Arctic. Chinese officials stress their country’s neutrality on the legal status of maritime passages to leave the door open for China’s entrance into potentially contested maritime territories in the Arctic. China cooperates with Russia’s regulation of the Northern Sea Route based on Arctic 234 of the Law of the Sea and does not challenge Russia’s straight baselines claiming the area as historically Russian internal waters. Erdem Lamazhapov, Iselin Stensdal and Gørild Heggelund of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute write about China’s Polar Silk Road and China-Russia cooperation under changing political conditions.

The Chinese scholars I met emphatically criticized the “paranoid” view that a Chinese military presence in the Arctic is inevitable. The first objection, they say, would come from Russia, who has its own powerful military complex in the Arctic and would not welcome Chinese interference or encroachment. China and Russia have amicable military relations, but the scholars expressed that China is not interested in military-level alliances after brush-ups of the twentieth century, such as the armed conflict between the USSR and China in 1969. China’s only defense treaty is with North Korea, signed in 1961. As the scholars told me, China may be interested in diverse partnerships but alliances are unlikely.

When it comes to Arctic partnerships, there are many opportunities to cooperate with China. However, the scholars also emphasized that collaboration over simply “climate change” is too abstract. Rather, lessons should be taken from accords such as the International Agreement to Prevent Unregulated Fishing in the High Seas of the Central Arctic Ocean, which would not have been possible without Chinese participation. China is becoming increasingly involved in Arctic scientific collaboration, notably with Russia.

Overall, I was fascinated by China and the sophisticated views of the scholars I met left a strong impression on me. China’s role in the Arctic continues to be a significant development in international politics and we will continue to produce research and articles on this theme.