Selling Stolen Land: A Reexamination of the Purchase of Alaska and its Legacy of Colonialism

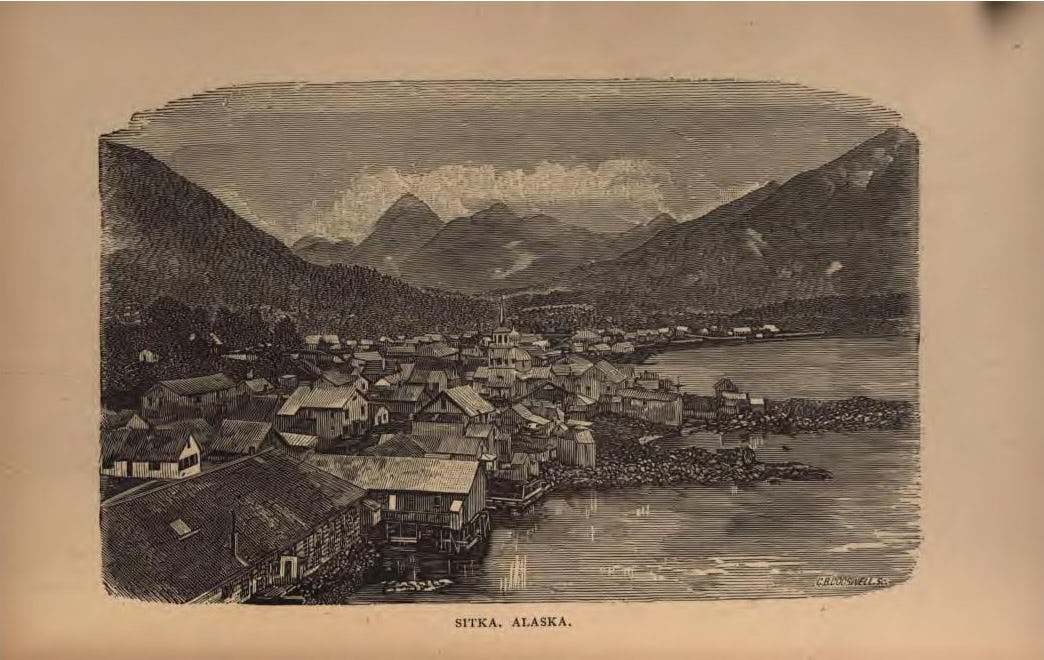

An illustration of Sitka, Alaska, completed in the 1870s, shortly after the Alaska Purchase. Photo: Sheldon Jackson

Indigenous peoples have inhabited the Arctic since time immemorial, establishing rich regional cultures and governance systems long before the introduction of modern borders. The Arctic Institute’s 2022 Colonialism Series explores the colonial histories of Arctic nations and the still-evolving relationships between settler governments and Arctic Indigenous peoples in a time of renewed Arctic exploration and development.

The Arctic Institute Colonialism Series 2022

- The Arctic Institute Colonialism Series 2022: Introduction

- Neo-Colonial Security Policies in the Arctic

- Brussels Looks North: The European Union’s Latest Arctic Policy and the Potential for ‘Green’ Colonialism

- Poverty, Well-Being and Climate Change in the Arctic: a Musical Perspective

- Colonialism and Reproductive Justice in Arctic Canada: The Neglected Historical and Contemporary Analysis of Genocidal Policies on Arctic Indigeneous Reproductive Rights

- The Delicate Work still undone in the Church of Sweden’s Reconciliation Process

- Selling Stolen Land: A Reexamination of the Purchase of Alaska and its Legacy of Colonialism

- The Old Colonialisms and the New Ones: The Arctic Resource Boom as a New Wave of Settler-Colonialism

- China, Circumpolar Indigenous People and the Colonial Past of the Arctic

- Language, Identity, and Statehood: A Brief Insight into the History of the Minoritization of the Komi People

- Russia’s Colonial Legacy in the Sakha Heartland

- How to Develop Inclusive, Sustainable Urban Spaces in the European Arctic and Beyond – Insights from Kiruna

- The Arctic Institute Colonialism Series 2022: Conclusion

In March 1867 the United States agreed to a proposal from the Russian minister in Washington to purchase the territory of Alaska for $7.2 million dollars. Negotiations were spearheaded by Secretary of State William Seward who believed Alaska’s greatest value was as a trade link between the United States and Asia. A common misconception in American history is that the purchase of Alaska was widely unpopular. The phrase “Seward’s Folly” is often associated with the decision, but in truth, the purchase was almost unanimously viewed favorably across national newspapers.1) In addition to being an economic bridge to Asia, the territory of Alaska was seen as a stepping-stone to further American expansion as well as a buffer against European interests in North America. A subsequent benefit of Alaska included the swaths of resources of timber and fish (and later gold and oil).2) For Russia, selling Alaska alleviated financial costs of the Crimean War and, most importantly, unburdened them from a region virtually impossible to defend against growing British and American ambitions.

For the two powers involved the exchange of the territory was seemingly without any controversy or second-thought, but noticeably absent from the discussions were the indigenous tribes of Alaska. At no point during the negotiations were any Alaska Natives present or consulted. Rather, Alaska Natives were ignored, despite both Russia and the United States knowing that overseeing the territory would require governing a large indigenous population. The ignorance did not stop with the issue of sovereignty, but extended to indigenous culture and population. It was not until 1880 that the first American census of Alaska was taken, and although it was impossible to visit every part of Alaska, the results revealed a total population of 33,426 of which only 430 were not indigenous.3) The indigenous population, especially in the farther north and interior regions, was likely larger, even in 1867.

Although the United States was not concerned with the Alaska Native’s opinion of the transfer, the reverse was not often true. In Sitka, the seat of the U.S. government’s Department of Alaska, the Tlingit population did not hesitate to voice their displeasure with their new occupiers. The U.S. Army commander in Alaska, General Jefferson C. Davis (no relation to the Confederate president), complained that many Tlingits would “frequently take occasion to express their dislike at not having been consulted about the transfer of the territory.”4) Sympathy or remorse however, was in short supply. The overwhelming attitude towards Alaska Natives was that they were a hindrance towards white settlement and development. Early military reconnaissance of Alaska reported that settling in certain regions of the new territory, especially farther north, was likely to be resisted by the indigenous population. The solution, recommended to General Henry Halleck, commander of the army’s Division of the Pacific, and now in charge of Alaska, was that “a show of military power be made at the earliest practical moment.”5) Two years after the purchase tensions between the occupying U.S. army and the Alaska Natives finally reached a breaking point.

In January 1869, in what has been described as “an incredibly stupid act of feigned camaraderie,” General Davis invited three well-known Tlingits to his government quarters and gave them each a bottle of whiskey to celebrate the new year.6) Later that evening, soldiers came across the three Tlingits drunk outside the customs house and attempted to shoo them away. A fracas ensued during which one Tlingit, a young man named Cholckeka, stole a soldier’s rifle and escaped through the gate out of Sitka. When the incident was reported to General Davis the next morning, he ordered Cholckeka to be arrested and the gun recovered, but when soldiers entered Cholckeka’s village a scuffle ensued resulting in one soldier being shot. In response, four heavily armed ships moved into Crescent Bay and aimed their guns at the Tlingit village, which was home to over nine hundred Tlingits, a majority of whom were women and children. General Davis stood on a nearby parapet and prepared to give the signal to fire by holding out a white handkerchief. If dropped, the ships were to destroy the village. According to one soldier, General Davis teased dropping the handkerchief a number of times before Cholckeka finally agreed to surrender and spend thirty days in jail. This, sadly, was only the beginning of a tragic episode between the Americans and Alaska Natives.

When the ships first anchored in Crescent Bay General Davis had given the order to shoot any Tlingit attempting to leave the village. After Cholckeka was arrested this order was rescinded. Unfortunately, news of the rescinded order was either not shared, or blatantly ignored. The day after Cholckeka’s arrest a soldier opened fire on a canoe that had pushed off the beach near the village killing two men, one a Tlingit, the other a Kake, as those living on nearby Kuiu Island were known. General Davis was undisturbed by the news and refused to acknowledge any error or wrongdoing committed by the soldier. The Tlingit however, expected reparations either in the form of money or trade-goods for the deaths of the two men, as was customary in many indigenous cultures throughout Alaska. As customs dictated, if reparations were denied, which in this case they were, the penalty could be imposed on relatives, or members of the offending party’s clan. When no reparations were offered the penalty fell upon two random and unfortunate white prospectors who were killed to even the debt.

Ironically, the U.S. military enforced a similar code. General Halleck had issued an order stating: “If any member of a tribe maltreat a citizen of the United States the whole tribe and especially its chief will be held responsible for the offense,” but the U.S. army failed to recognize the irony of Alaska Natives holding military to the same standard.7) Rather, General Davis believed this incident was the perfect opportunity to finally display a show of military power against the indigenous population. He commandeered a small steamship called the Saginaw and headed towards Kuiu Island to demand the surrender of the individuals responsible for killing the white prospectors. The Kakes however, had seen the Saginaw approaching and evacuated the village. When Davis arrived and found the island abandoned he ordered the entire village, containing twenty-nine houses and numerous canoes, to be burned.8) Thankfully, it remains unlikely that any Kake were killed during this attack, but the ruthlessness of the U.S. response demonstrated not only an ignorance of indigenous customs but also an unwillingness to extend equal protection under the law to the Native American population.

This brief snapshot of Alaskan history was unfortunately not a singular occurrence. Throughout the early period of American occupation there were a number of similar instances of Alaska Natives being killed by white settlers or soldiers; the U.S. military refusing to hold the killers accountable, and Alaska Natives being forced to seek justice or reparations on their own. After which, as in the case of Kuiu Island, the U.S. would respond violently and forcefully. These interactions between the U.S. military and the Alaska Natives were a microcosm of the relationship between the United States and indigenous people in the nineteenth century. It was believed that indigenous sovereignty had to be subdued by force because Native American culture was incompatible with white American values like capitalism, Christianity, and individualism. What often ensued was a process of forced assimilation, as well as physical relocation to reservations, as means of subduing indigenous identity.

Sadly, the legacy of this colonialism remains evident in the twenty-first century, most notably in the propensity to ignore indigenous voices. Those studying the Arctic must recognize the connection between the past and the present and realize that the concerns of indigenous communities continue to be overlooked today just as they were preceding the purchase of Alaska. Indigenous voices serve as crucial guides towards a deeper understanding of human experience. The inclusion of such voices, not reluctantly as afterthoughts, but eagerly as remedies, is necessary and ought to be done so always and automatically. The purchase of Alaska marks America’s origin as an Arctic nation, but the ignorance towards Alaska Natives warrants a reexamination of this event and what it means for the United States to be an Arctic nation. Additionally, the myth of the purchase of Alaska being a folly ought to be reexamined as well. Almost certainly the purchase of Alaska was, indeed, unpopular. Unpopular among those who lived there long before Russians and Americans arrived on Alaska’s shores.

Samuel Kramer is a recent graduate of Montana State University, earning a Master’s degree in History. With areas of focus including the Arctic, Alaska, and the American West, Samuel hopes to begin a career researching, studying, and writing about the Arctic.

References