Knowledge is Power: Greenland, Great Powers, and Lessons from the Second World War

Members of the German weather station Edelweiss II taken prisoner by US Army soldiers, 4 October 1944. Photo: Unknown US serviceman

Much recent discussion has focused on the contemporary militarization of Arctic and subarctic regions. Journalism and scholarship alike question if military conflict might occur, how peace can be maintained, and what war would look like in the Arctic. To provide insight on such queries, The Arctic Institute’s 2021 Conflict Series provides analysis on past Arctic militarization and military activities—seeking both historic context and lessons learned for modern Arctic politics.

The Arctic Institute Conflict Series 2021

- The History and Future of Arctic State Conflict: The Arctic Institute Conflict Series

- Fisheries Disputes: The Real Potential for Arctic Conflict

- Environmental Détente: What can we learn from the Cold War to manage today’s Arctic Tensions and Climate Crisis?

- Knowledge is Power: Greenland, Great Powers, and Lessons from the Second World War

- The Impact of the Post-Arms Control Context and Great Power Competition in the Arctic

- The Arctic Institute Conflict Series: Conclusion

In 2019, when President Donald J. Trump confirmed that he was considering an attempt to buy Greenland, European leaders looked on bemused and amused. There were many reasons why Trump’s real-estate proposition was flawed: not least because Greenland is a proud nation within the sovereign Kingdom of Denmark and is most decidedly “not for sale”.1) Yet it is understandable why the president found this idea alluring. Greenland is, and has long been, geographically important to the United States, sitting in between North America and Europe. Eighty years ago, this meant that Greenland was caught between the US and its German enemy. Today, Greenland sits between the US and its Russian foe. In an increasingly warming, active, and re-militarized Arctic – where Russian military activity and controversial Chinese economic encroachment frustrate American and European allies – Greenland has taken on renewed importance. Indeed, there are lessons about the importance of Greenland that we can learn from its role during the Second World War.

The Weather War

From stormy seas and blustering gales, to perilous storms and dense fog, weather has always played an important role in war. If it’s too choppy, the landings can’t take place; if the cloud cover is too thick, the bombing won’t be as accurate; if it floods, the supply lines might be cut off; and, of course, if an extremely harsh winter is on the way, you might not want to invade Russia. It is for this reason that being able to reliably predict the weather is an important and valued commodity in times of conflict. This was no different during the Second World War. From the D-Day landing, to the bombing of Hiroshima, weather forecasting played a direct role in ensuring maximum military effectiveness and the achievement of mission aims.2)

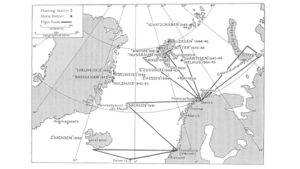

It is here that the importance of Greenland as a strategically vital information gathering hub comes to the fore. From a meteorological perspective, Greenland is a ‘breeding ground’ for western Europe’s storms. This fact was not lost on the warring nations during the turbulent period between 1939 and 1945, where any weather stations and patrol vessels that could sustain the harsh and unforgiving Arctic would become vital early warning stations for informing military planners of incoming inclement weather.3)

It is strange to think of, what was essentially common information for civilian populations prior to the war, becoming subject to censorship and confidentiality. Yet, this information was ‘prized intel’ and could have aided Axis powers in their planning of operations. It could have also offered them an extra tool in their assessments of windows for allied operations. Fortunately for the allies, with the outbreak of the war, Nazi Germany’s information nodes on weather reporting were severely reduced as they had largely relied on weather reports from allied countries prior to war breaking out.4) To maintain this meteorological advantage, the allies had to keep Nazi forces out of the Arctic and away from Greenland.

It is hard to overstate just how important weather information was to the allies. RAF commands, especially the RAF Bomber and Coastal Commands, were dependent on meteorological advice for all of their planning and operations. It was also important for estimating agriculture production in Britain as the country was under rationing. In addition, one of the most important contributions made by meteorologists to the allied war effort was to inform on the timings of the Normandy landings in 1944. The parameters for the landings were when moon and tide conditions were favorable on just three specific summer days; the 5th, 6th and 7th of June.5) Information supplied by meteorological stations on Greenland was key to making sure the allies got the day, the time, and the weather exactly right for crossing. Bad weather, and rough seas, would have been disastrous for allied forces, and small landing craft, making their way onto reinforced beaches. Overall, it was for these reasons that there was a secret ‘Weather War’ in the Arctic, and especially around Greenland, as the allies sought to maintain their advantage.

The Coming Storm: 1939-1941

At 2,166,086 sq km, Greenland is a vast island. It has a coastline that is “longer than the distance around Earth at the equator” at more than 27,000 miles. Along with the harsh Arctic weather, and difficult terrain, its sheer size means that Greenland is difficult to reliably and comprehensively patrol all year round. During the Second World War, therefore, it was a constant worry for the British and the Americans that the Germans could be operating clandestinely, establishing both manned and automatic weather stations along the Eastern coastline of Greenland. This worry was not without reason.

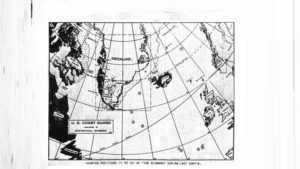

By April 1941, President Roosevelt had extended the US neutrality zone to include Greenland and the Azores, which allowed the US Navy to patrol the western Atlantic and broadcast the location of German ships to the British.6) Despite the fact the United States was not officially in a state of war with Germany at this point, a confrontation best described as ‘below the threshold of war’ existed. As such, the United States, in cooperation with the allied powers, tried to deny German efforts to operate effectively in North Atlantic and in Greenland.

For the United States, deciding how to decrease the flow of meteorological information to Germany was not without its problems. Greenland was still part of the Kingdom of Denmark, despite Denmark being occupied by the Nazis from 1940. As such, there was the difficult political matter of some weather stations on the eastern coast of Greenland still conveying data back to mainland Denmark, but also Norway which was also occupied. The stations were run by Danish and Norwegian crews so they were seemingly under Danish control. Due to the occupation, however, it appears their allegiance was severely in doubt. As the historian JDM Blyth detailed not long after the war;

“[…] even after the German occupation of Denmark and Norway, weather reports continued to be transmitted from Danish weather stations in East Greenland at Angmagssalik, Scoresbysund, Ella Ø and Mørkefjord, and from Norwegian stations at Myggbukta and, in south-east Greenland, at Torgilsbu. The problem thus presented to the warring States was one of some delicacy; by whom were these stations to be maintained, and to whom were they to transmit reports?”7)

The Germans had tried to capture these stations early on in the war, but the Danish and Norwegian ships chartered to ferry them across to Greenland in a less conspicuous fashion were intercepted by the British off the Greenlandic east coast. Good information sharing between the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, was key to detecting the German attempts to establish these weather stations and ensure the Germans were always kept under pressure in the region. Due to these efforts, Germany lacked reliable and consistent metrological reports from the Arctic.8)

However, astonishingly, some German weather stations were set up on the island and, in order to counter this German presence, a novel plan was set afoot. It was in the summer of 1941 that it was decided between the United States and the local government of Greenland, under Eske Brun, that a joint allied group was to be created, namely the North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol, one of the world’s first cold weather special forces units. The unit’s composition was made up around 10-15 Danes, local Greenlanders, and Norwegians who were familiar with the terrain and keen to defeat the Germans.

Their core task was to function as a long-range reconnaissance unit for detecting any German incursions. When they did stumble across hidden bases, they would relay this information back to the US Army Air Force, where sorties would be launched from air bases in Iceland or Bluie East Two (located in Ikateq fjord in Greenland) to target and destroy the site of the intruding Germans.9) As an example, one of the largest manned German weather stations was codename “Holzauge” and was established in late August 1942 at Hansa Bay. To the surprise of the allies, and perhaps the Germans themselves, this remained undetected until March 11th, 1943, when it was revealed by a North-East Greenland Sledge Patrol.10) In what was the first confrontation on Greenland, a German patrol from “Holzauge” engaged the sledge patrol where one Dane was killed.

In the end, there were a total of four German weather stations on Greenland during the war, some of which were only routed out thanks to the deliberate and focused allied project to build covert listening stations in the region to pin-point the signal of these German stations and locate transmission hubs along the vast Greenlandic coast. These were located in places like Jan Mayen, a small volcanic Norwegian island in the Arctic Ocean, off the east coast of Greenland. It housed a Free Norwegian weather station which transmitted to the British and saw the Germans mount failed seaborne and airborne attacks on the island. From 1943, however, Jan Mayen was also home to a US radio surveillance station called “Atlantic City”. This station aided in the location of German radio and weather stations on Greenland, highlighting just how important knowledge and information gathering in the Arctic can be to ensuring the allied advantage.11)

Fear of German raids

Clandestine weather stations were but one of the many German threats in the Arctic region in and around Greenland. German naval activity was also of concern to the allies. Early on in the war (May 1941), the German cruiser Prinz Eugen and the famous battleship Bismarck had sailed through the Denmark Strait, in-between Iceland and Greenland. This was detected off Greenland and worried the Canadian government who conveyed to the United States that, with such an operational reach, the German military was now in range of, and could potentially raid, valued Canadian assets on Greenland.

This included the mine at Ivigtut in southern Greenland, which was used to obtain the rare earth mineral cryolite, used in the production of aluminium.The fear was that “one well-directed shot from the deck gun of a German submarine or a clever act of sabotage by one of the workmen could have seriously damaged the cryolite mine […]”.12) This would have had major implications for the aluminium supply chain in Canada, the production of military aircraft in which the aluminium was used, and ultimately the allied war effort.13)

This concern from the Canadians led to an increase of their military garrison at the mine from 100 to 480 personnel. The Germans did not, however, end up disrupting the mine, nor did they deploy saboteurs. It is not entirely clear why this was the case. One theory is that Germany did not want to incite further reasons for US intervention in the early stages of the war, although this is unlikely as the Germans were engaging occasionally with US ships in the Atlantic prior the official US entry into hostilities. Nevertheless, there is no indication that German commando raids were calculated in German war plans. It may very well be that the allied fears of raids against strategic targets in Greenland were a product of mirror-imaging rather than actual intelligence on German capabilities for carrying out such special operations. Nevertheless, if Germany had seized the initiative, as was feared, then it could have disrupted the allies.14)

This fear was especially potent in the early years of the war, until 1943 at least when the reliance on the mine decreased due to the rise of synthetic cryolite.15) This fear was also precipitated by the fact that the German Navy’s U-boats were able to operate with relative freedom in the North Atlantic and were vital in helping to covertly move Axis personnel under the nose of the allies and establish additional weather stations on Greenland.16)

Lessons for today

It would be wrong to present the context of the Arctic during the Second World War and the current situation as synonymous, but there are certainly parallels and lessons to learn. Some challenges in maintaining situational awareness over the vast area of the Northern and North-eastern parts of Greenland can be seen today, as can the strategic importance of Greenland to the United State and the threat of troublemaking actors into the region. Indeed, Secretary of State Blinken’s visit to Greenland in May 2021 reinforced the continued importance of Greenland to the US under the Biden administration.

The struggle during the Second World War in the Arctic, and Greenland’s strategic position in it, was, however, an overall intelligence struggle. It was as much about detecting what potential move the opponent would make and how to counteract those moves, as it was about reliably predicting the weather. Indeed, surveillance and obtaining situational awareness becomes especially important in areas that are susceptible to possible intrusions. This was reinforced during the Cold War when acoustic and sonar sensor systems were placed in the GIUK gap in order to limit Soviet submarines from traversing into the Atlantic. Such lessons may have been forgotten after the Cold War, but are now being quickly relearnt.

President Trump’s plans may not have come to fruition during his tenure, but his public bidding was a wake-up call for the Danish Government. Although “[i]n the vast majority of areas, authority has now been devolved to the home rule government of Greenland. Other areas, including foreign defence and national security policies…remain the responsibility of the Danish Government and Parliament”.17) This is a responsibility that the Folketinget (Danish Parliament) has reengaged in with renewed energy and vigor in recent year, and indeed months.

In February 2021, the Danish Minister of Defence, Trine Bramsen, announced that the country would invest 1.5 billion DKK (245 million USD) in strengthening its defense capabilities in the Arctic.18) In the face of growing Great Power interest in an ‘opening Arctic’ it is no surprise that Denmark wishes to reinforce its defense capacity in the region. Half of the allotted budget will go towards military surveillance drones to improve information and intelligence gathering off Greenland.19) As such, it has not escaped the Danish attention that action was needed to ensure the Danish government, and its military, can remain sized of the ongoing security situation in the Arctic.20)

As Defence Minister has Trine Bramsen, stated, “…when there are large areas that we cannot keep an eye on, it can tempt foreign powers to pry around where they should not”.21) This accusation is not without substance. There have been “abnormal activities” reported in and around the GIUK Gap and the Danish government are keen to ensure that any activity is not left unsupervised and can be responded to when required.22)

This is also useful for NATO, of which The Kingdom of Denmark is a key alliance member, and most specifically to the United States. Until now, Denmark has only had “one aircraft, four helicopters and four ships”, along with a sled patrol, to monitor the region.23) As such, new significant Danish investment in large, unarmed, long distance Medium Altitude Long Endurance drones (of which there will be two), smaller ship launched UAVs, the re-establishment of a Cold War-era radar station on the Faroe Islands, and previously announced space based capabilities (satellites), will work hand in hand with existing NATO capabilities in Iceland, the UK, Norway, the US, and Canada, to provide a coordinated system of information gathering and surveillance on potentially unfriendly activity in the region.

Such investment has been looked on favorability by the US. As Secretary Blinken remarked, it is “important and significant that Denmark is making significant investments in what we call domain awareness, situational awareness, making sure that in the North Atlantic and in the Arctic, we have the technology, the resources, the personnel to know what’s happening, who’s doing what at any given time”.24) As lessons from the Second World War teach us, knowledge is power and the information gathered between 1940 and 1945 helped keep track of German military activity and provide metrological information to the allies. Today, the new Danish military surveillance and intelligence gathering systems that are based on in the Arctic will help keep all NATO allies secure and sized of developing situations. Without proper situational awareness in the Arctic, the dynamics of information asymmetry could escalate tensions further, with a higher chance of miscalculation and misunderstanding. As the Danish defence minister has argued, the increased surveillance capabilities should be seen as a contribution to “de-escalation” but also as legitimate enforcement of territorial integrity. As we have seen, this is not the first (and it will not be the last) time that Greenland has served as an important region for the security of Western allies.

Michael Gjerstad is a PhD Candidate and Member of the Center for War Studies at SDU in Denmark. He specialises in Russia’s military transformation processes and the way culture affects how military change is implemented. Michael’s other research interests include the development of Russian special operations forces, the Arctic, and NATO resilience and deterrence. Dr. James Rogers is DIAS Assistant Professor in War Studies, within the Center for War Studies, at SDU in Denmark. He is also an Associate Fellow of LSE IDEAS (London School of Economics, UK) and an IAS Arctic Geopolitics Spotlight Fellow (Loughborough University, UK). He presents the History Hit Warfare podcast.

References