Perils of the Familiar Past: Explaining the United States’ South China Sea Misanalogy

Then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo delivering a speech ahead of the Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting in Rovaniemi, Finland, on May 6, 2019. Photo: Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland

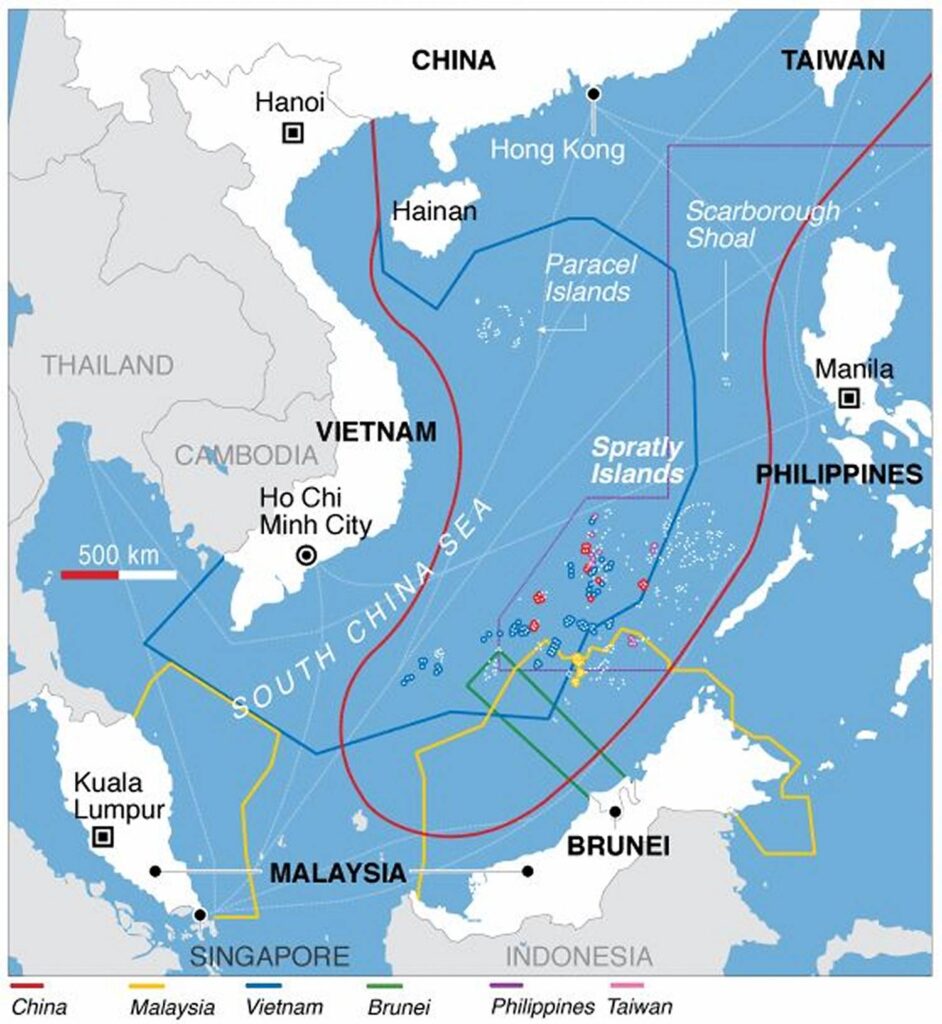

China, a non-Arctic state…has challenged international law in the East and South China Seas, built islands, and claimed territorial status to suit its national interests. China’s pattern of behavior in the Indo-Pacific region and its disregard for international law are cause for concern as its economic and scientific presence in the Arctic grows.1)

One would not be alone if they mistook the above for then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s infamous maiden speech at the Arctic Council in 2019. It could very well have been the case. After all, at first glance, it seems to merely be a politer version of Pompeo’s inflammatory question that cast the Arctic newcomer China as expansionist—“Do we want the Arctic Ocean to transform into a new South China Sea, fraught with militarization and competing territorial claims?”, he asked an understandably nonplussed audience ahead of the Rovaniemi Ministerial Meeting.2)

Recognising the quote’s true origins only deepens the mystery. Prominent Arctic observers like The Arctic University of Norway’s Marc Lanteigne have already repudiated Pompeo’s specious analogy, dismissing it as a “distraction from actual…problems” like climate change.3) Among other notable differences, China does not have any historical claims to Arctic territory. Neither are there active territorial disputes left in the region, ever since the Hans Island quarrel was resolved in 2022.4) If Pompeo’s analogy was indeed a logical fallacy, why did the USCG—the U.S.’s “primary maritime presence in the polar regions”—enshrine it into its standing Arctic Strategic Outlook of 2019 (henceforth Strategic Outlook)?5)

This decision was no minor one. The document establishes the USCG’s long-term strategic objectives for the Arctic, which will be gradually implemented into the foreseeable future according to a follow-up Arctic Strategic Outlook Implementation Plan (henceforth Implementation Plan), released in October 2023.6) In other words, this problematic threat perception is already shaping policy.

The deliberate inclusion of the analogy suggests that the past is ‘useful’ for making sense of the present. Political Scientist Yuen Foong Khong instructively observed that “statesmen have consistently turned to the past in dealing with the [novel] present” as a cognitive heuristic.7) What is this “novel present” that motivated the use of historical analogies? While the U.S. is no stranger to the Arctic, the circumpolar front had lacked dedicated strategic attention amid urgent priorities in the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. One could blame this attention deficit on the fact that only the non-contiguous Alaska is in the Arctic.8) Success had evaded Arctic Caucus co-chairs Senators Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Angus King (I-ME) until climate change had irrevocably transformed the Arctic into a region of “increasing strategic competition”.9) Geopolitical competition in the Arctic is not new, though—look no further than the Aleutians Campaign of 1942–1943, the Soviet-Finnish Wars between 1939–1940 and 1941–1944, or even the Cold War. What is novel is its occurrence in a melting Arctic. In fact, the U.S. was a latecomer to the conceptualising this emerging space. As early as 2014, Chinese academics had already begun to characterise the Arctic as a “strategic new frontier” (zhanlüe xin jiangyu 战略新疆域).10) China’s unprecedented interest in the Arctic renders the present even more novel.

The immediate experience of abrasively interacting with China in the South China Sea has become an unshakable precedent for U.S. strategic thinking. As mentioned earlier, there is already a rich body of incisive critique that rejects the merits of the analogy based on current observations. While it would be foolhardy to categorically dismiss any possibility, however remote, that debate is all but settled for the near term. Instead, this article draws from the fields of applied history and political psychology to understand the before and after of the analogy: how, and to what consequence, have U.S. strategists used and abused history to conceptualize the Arctic domain and strategise moves to secure its national interests? While I do not pinpoint historical analogising as the sole determiner of U.S. Arctic policy—Russia’s re-opening of Cold War-era bases along its Northern coastline is likewise disconcerting—the evidence I present below suggests it certainly had a strong influence.11)

The balance of this article proceeds in three sections. First, I briefly survey existing literature on analogical reasoning and the broader field of applied history to set the theoretical context. Next, I trace the process by which the South China Sea analogy took hold of U.S. Arctic strategic discourse, beginning in 2017. I conclude by analyzing the consequences of acting on the assumption that the misanalogy is true.

Applied History and Analogical Reasoning

Applied History is a burgeoning field of study that investigates how historical reasoning could or should influence decision-making. This framing rightly suggests that the field deals with both empirical (how it influences decision-making) and normative questions (whether it should be used for it).

Jay Mens instructively subdivided applied history into two methods: genealogy and analogy.12) Genealogy trawls the historical record in an attempt to answer “how did we get here?”—a process that helps “identify the most important variables in a situation” such as the key reasons for a conflict and factors that could exacerbate or mitigate it.13) Analogy, on the other hand, involves comparing “the structures of two [similar] situations” to draw insights for a novel context.14) Ernest May and Richard Neustadt pioneered the productive use of analogical reasoning at the Harvard Kennedy School.15)

Mens’s approach to asking the normative question of how history can be effectively used is illuminating insofar as we can wield genealogy and analogy as instruments. This is not a given. After all, as he recognizes himself, analogising—however poorly done—is “an innate predisposition” native to human psychology.16)

This article takes an interest in the empirical: problems arising from the instinctive retrieval of history for decision-making. It is well established in psychological literature that human beings young and seasoned instinctively rely on analogies with “surface similarities” to make sense of novel situations.17) They are helpful mental shortcuts to overcome “limited cognitive capacities”.18) Experimental studies found that children are capable of selecting tools they have encountered before to solve new problems.19) They do not just draw perceptual similarities (similar appearances), but also relational ones (similar functions).20)

As for decision-makers, they often “go beyond the information given” in drawing inferences, and these false conclusions tend to be sticky.21) A helpful distinction here is between “the past” and “history”. While “the past” refers to what transpired before, “history” is a particular interpretation of the past (since a perfect recount is humanly impossible). Therefore, decision-makers often draw inferences from their understandings of a historical episode, which is apt to being bent out of proportion.

Indeed, the central puzzle of Khong’s seminal work, Analogies at War, is why some of the most “historically conscious” advisors led Lyndon B. Johnson into the debacle that was the Vietnam War.22) The Analogical Explanation (AE) framework was his answer. While analogies could be used for rhetoric, Khong posits that policymakers also utilize history to perform six diagnostic tasks ranging from defining the situation to providing policy prescriptions.23) Yet, the tendency and temptation to rely on analogies—poor ones at that—accounts for the disastrous decision in 1965 to intervene militarily in Vietnam. Johnson’s advisors often cited the failure to appease Hitler as a warning not to compromise with the insatiable.24)

Were similar mistakes made in the Arctic? Since analogical reasoning is a fault of human psychology, the answer is expectedly: yes.

Retracing the Missteps

One might understandably assume that the South China Sea analogy began and ended with Pompeo. After all, the analogy most famously appeared in his Arctic Council speech. Pompeo’s harrowing prognostications suggest the possibility of a one-to-one replication of gray-zone South China Sea conflicts in the Arctic. One might be tempted to dismiss Pompeo’s pontifications as unduly alarmist—a use of analogies that fall under what Khong functionally categorizes as “advocacy” rather than for “diagnosis”.25) But that would be a mistake.

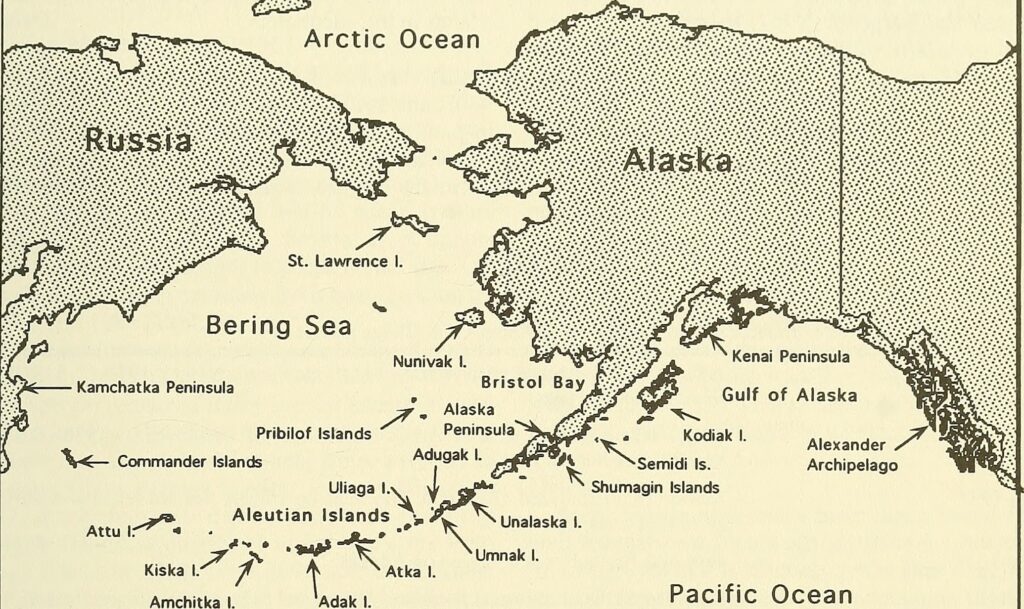

The South China Sea analogy was actually first invoked in 2017, long before Pompeo’s catastrophising. To be sure, connections were made between the two seas even earlier. Short of an analogy, retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral David Titley suggested in 2015 that America’s collected response to sighting Chinese warships off the Aleutians could have a “softening effect on maritime disputes in the South China Sea”.26) While political scientists have also suggested in the same year that the Arctic Ocean governance regime could be instructively applied to overcome South China Sea disputes, 2017 was the first instance where the analogy was applied in reverse.27)

At a Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) dialogue, then-Commandant of the USCG Admiral Paul F. Zukunft warned that “as I look at what is playing out in the Arctic, it looks eerily familiar to what we’re seeing in the East and South China Sea”.28) He was referring to Russia’s filing of sovereignty claims in the Arctic Ocean and China’s icebreaker Snow Dragon (Xuelong 雪龙) performing research on the extended continental shelf. This sentiment was echoed at the tactical level too. In 2023, Capt. Stephen Adler, then commander of the USCG Cutter Stratton, warned that “if we’re not there and we allow them to test our waters, it starts to look more like the South China Sea”.29)

To be sure, other historical analogies like “Cold War at the North Pole” and “Ice Curtain” have also been employed in public discourse, but the “South China Sea” was uniquely invoked by representatives of the U.S. government.30)

I acknowledge steel-man arguments that the analogy may actually be a calculated public diplomacy strategy, mere rhetoric, or a viewpoint exclusively held by the USCG. Charitably, the U.S. may have genuine concerns about Chinese sovereign ambitions in the Arctic, and therefore actively used the analogy to securitise an otherwise peaceful region and thereby counsel vigilance among Arctic states. This point on long-term prudence, while understandable, accords excessive credit to U.S. strategy. The evidentiary record suggests room for mistakes too. As for the other two rebuttals, the staying power of the South China Sea analogy in broader strategic discourse—whether in public or private, in speech or writing—suggests that there must be a deeper basis for this misstep.

For one, during a private diplomatic meeting in May 2018, then-Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis drew a similar comparison. After meeting with Mattis at the Pentagon, then-Danish Defence Minister Claus Hjort Frederiksen recalled to Danish broadsheet Jyllands-Posten that “Mattis reported that the Chinese are very active in the South China Sea. They had promised that what they were building on these artificial islands had nothing to do with defense. But three weeks ago, the Chinese sent long-range strategic bombers to these islands, breaking their promise”.31) “The parallel,” Frederiksen warns, “was of course that this could also be expected elsewhere—including Greenland”.32) Mattis was concerned about the Nuuk and Ilulissat airport projects, for which the state-owned China Communications Construction Company had submitted a generous bid to an overjoyed Greenlandic government seeking economic independence from Denmark.33)

Later in 2019, the analogy was institutionalized in the USCG’s Strategic Outlook. This standing strategy—the first and latest since 2013—similarly invokes the South China Sea as a predictive analogue. Two specific diagnostic claims were made, one on challenging territorial sovereignty and another on impeding freedom of navigation:

China…has challenged international law in the East and South China Seas, built islands, and claimed territorial status to suit its national interests. China’s pattern of behavior…and its disregard for international law are cause for concern…China’s attempts to expand its influence [referring to dispatching ice-class vessels] could impede U.S. access and freedom of navigation in the Arctic as similar attempts have been made to impede U.S. access to the South China Sea [emphasis mine].34)

The use of two phrases is striking: “pattern of behavior” and “similar attempts”. These two conclusions assume that China would pursue the same ends in the Arctic as it did in the South China Sea, with similar ways and means. The analogy did not just inform threat perceptions, but also two of the three proposed “lines of effort”: “Enhance Capability to Operate Effectively in a Dynamic Arctic” and “Strengthen the Rules-Based Order”.35) The collective aim is to enhance the USCG’s ability to counter threats to the Arctic order.

The analogy is not a Trump aberration, because the Implementation Plan—which provides detailed guidance for realizing these “lines of effort”—was published under Biden’s watch. Of the 14 proposed initiatives, the first 5 are concerned with expanding operations and building relevant capacities. Recommendations for enhancing diplomacy came after. The very first initiative stressed the need to “assert [USCG] presence” at “joint and combined Arctic operations and exercises” with “a mixture of air and surface assets”.36) The next four initiatives called for new icebreakers and improving Marine Domain Awareness (MDA) through investments in aviation and satellite communications. These investments are needed “to mitigate the heightened risk created by climate change, increased human activity, and strategic competition in the Arctic”—referring to Russia and China.37) The goal of MDA is to gather and synthesize information on the “positions and intentions of all vessels” and its “crew, passengers, and cargo carried”.38) While vague, these capabilities clearly have both military and civilian uses in mind.

Taken together, the Implementation Plan appears to at least be partly aimed at countering Chinese presence in the Arctic. The South China Sea analogy, while not the exclusive influence, certainly oriented the initiatives toward shows of force. This uncompromising approach has ushered in a host of issues.

When Vigilance becomes Overcaution

First, this false analogy unproductively links the two waterbodies. We observe hints of this in diplomat spats between the U.S. and China. Responding to Pompeo’s 2019 speech, China’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying pushed back against Pompeo’s criticism that the Arctic was too far from China for it to be relevant. She riposted that “Mr Pompeo is not bad at calculating distance…has he ever measured the distance between the continental United States and the South China Sea?”—implying that the U.S. had a weaker case to operate in the South China Sea, which was even farther away.39) She also pointed out a key difference: while the U.S. catastrophises about Chinese militarising the Arctic, they were already doing so in the South China Sea.40) Setting aside the substance of her rebuttal—the U.S. territories of Guam and Hawaii are both in the Pacific—the analogy clearly hands China both the motivation and justification to operate (retaliatory) far-seas patrols in equal measure.

This causal chain was not lost on the Americans. Commenting on the PLA Navy’s Arctic operations in 2021, Troy Bouffard from the University of Alaska Fairbanks observed that “we’re probably starting to frustrate them a little bit, maybe, with the South China Sea issue”—he was referring to U.S. exercises conducted there.41)

Second, harping on the analogy risks drawing Russia and China together—a cardinal error made during the Cold War. Chinese warships were spotted performing Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) near the Aleutians in 2015 and 2021.42) Each time the USCG reported that they complied with international law. Yet, the Strategic Outlook assumes that Chinese and Russian ambitions are similar—to assert sovereignty in the Arctic. Since 2022, and most recently in August 2023, there have indeed been Sino-Russian joint patrols near the Aleutians.43) One might contend that such unprecedented cooperation simply reflects the broader geopolitical picture of U.S.-China great power competition and the ongoing Russo-Ukranian War.

That interpretation is valid but incomplete. The misanalogy enables this wider trend of Sino-Russian alignment to find expression in the Arctic space. To persist on this path risks provoking more Chinese-Russian FONOPS. The state-owned Global Times reported that the 2023 patrol was “not first, not last (sic)”, with a PLA expert warning that “the Americans should get used to it”.44)

Finally, it misdiagnoses the root causes of Chinese Arctic presence. The Chinese themselves have promoted the regional vision of a Polar Silk Road since January 2018, linking the region to its broader Belt and Road Initiative.45) Such geoeconomic overtures may, admittedly, assume geopolitical significance if specific infrastructure built turn out to be dual-use. However, extending that threat perception to sovereignty claims would be one step too far.

Chinese charm offensives are far more attractive than supposed coercion because the Arctic suffers from infrastructural gaps. Greenland’s enthusiasm for Chinese airport investments is thus unsurprising. In fact, the National Strategy for the Arctic Region (2022) recognizes this multifaceted threat: “China seeks to increase its influence in the Arctic through an expanded slate of economic, diplomatic, scientific, and military activities”.46) Therefore, it would perhaps serve U.S. interests better to pursue a regionally specific solution: perhaps an Arctic version of the Build Back Better World (B3W) policy rather than naval shows of force. As it turned out, once the U.S. and Denmark offered to fill the investment gap, the airport deal fell through in short order.47)

Concluding Thoughts

While the South China Sea misanalogy is not the only source of U.S. Arctic strategy, the marshaled evidence demonstrates that it has had an influence. Whether rhetoric or strategy, private or public, the misanalogy is rampant in U.S. strategic discourse. The USCG’s dominance in this discourse should not be read as an expected outcome of its raison d’être. Rather, it figures prominently precisely because the misanalogy helped dispose the U.S. toward naval shows of force.

Analogies are helpful when wielded, but they can be damaging if left unquestioned. Analogical thinking, when instrumentalized, can derive insights—as countless articles published in the Journal of Applied History demonstrate.48) Its instinctive use in statecraft, however, requires constant self-examination. Mutatis mutandis—the concept of making comparisons while accounting for necessary alterations—should be the aspiration.

It is rather fitting to observe that the Arctic region sits at the convergence of many different timezones. In a metaphorical sense, various states looking into this ever-evolving region have introduced their own senses of time and history to conceptualizing it. We also see this temptation elsewhere: from labeling U.S.-China competition a “New Cold War” to casting Putin as the “New Hitler”.49) Recognising human psychology to be as such, it would perhaps be wise to reflect on our instinctive, but nonetheless disciplinable, use of analogies going forward.

Calvin Heng was formerly a Graduate Research Assistant at the Arctic Initiative, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School. The author would like to express his gratitude to Professor Fredrik Logevall, Dr. Eyck Freymann, Alina Bykova, and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

References