The EU’s new Arctic Communication - Part I

HR Federica Mogherini and Commissioner Karmenu Vella. Photo: European Commission

Part I: Deconstructing “integrated”: the nature of the “EU Arctic policy” and its limits

A new Arctic Communication from the European Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign and Security Policy is supposed to set the stage for an “integrated EU Arctic policy.” If taking the common understanding of the word “integrated” – making the policy more than just a sum of its many parts -, this policy is not delivering. Considering the nature of the cross-cutting Arctic policy—of marginal interest to the EU—we claim it is highly unlikely that this document will lead to enhanced coherence and integration. This is even more true as the Arctic, until recently considered geo-economically ‘hot’, may not be that attractive anymore due to low oil and other commodity prices such as minerals, as well as the sluggish rise in Arctic shipping.1) However, if assessed against other standards than “integration,” the EU’s perception of its place in the Arctic and its focus show a few clear signs of progress.

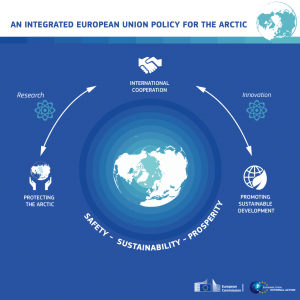

The new Joint Communication on “An integrated European Union policy for the Arctic” (JOIN(2016) 21 final) was published on 27 April 2016 and can be found here.

We scrutinize the new Joint Communication in three installments. Part I analyses the very meaning of an “integrated EU Arctic policy,” highlighting limitations and signs of progress. Part II discusses the most visible aspects of this progress: the EU’s approach towards the European Arctic and proposals for better coordination of EU Arctic affairs. Part III contextualizes the Communication in the broader circumpolar setting of Arctic cooperation and the Union’s upcoming Global Strategy.

The different parts were simultaneously published as one policy paper via the ArCticle series of the Arctic Centre (University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland) and can be found here.

Before we get too excited: words without meaning

In May 2014, the Council of the European Union—the EU institution that brings together representatives of the 28 EU member states—requested the European Commission and High Representative to work towards “further development of an integrated and coherent Arctic Policy”.2) The new Communication was therefore meant to develop the EU’s Arctic policy as an integrated one, and it dutifully does so in the title and throughout the text. However, despite these references, the policy update lacks a proper definition of what “integrated” actually means in the EU-Arctic context. To be blunt, even the academic community of EU (foreign) policy researchers tends to accept commonly used catchphrases such as “integrated,” “coherent,” or “overarching” without scrutinizing what stands behind these policy slogans.

Earlier, the authors of this analysis3) identified constraints for formulating a coherent and comprehensive framework governing diverse aspects of the EU’s presence in the Arctic. To put it simply, the scope and number of Arctic-relevant issues is too broad, their diversity too great and the position of Arctic affairs in EU policymaking too marginal for a coherent policy to emerge, i.e. one that produces synergies (with different Arctic-relevant actions supporting one another) between different Arctic-relevant actions. And the idea of “integration” could indicate an even more ambitious policy undertaking, making Arctic policy something more than just a sum of its parts. The challenge arises from the very nature of the EU Arctic policy, which incorporates a diversity of both internal and external issues. We focus on the former in Part II and on the latter in Part III of this analysis.

Integrated into one: a single Arctic policy?

Policy integration occurs in at least three varieties. First, integration can mean bringing different sectors together to form a single policy guided by one set of objectives. That has been attempted in fields such as rural policy,4) youth policy or the EU’s Integrated Maritime Policy (IMP). The latter is particularly instructive. Although analysts have often criticized that fisheries, environmental policy, maritime transport, regional development, and offshore energy still go their own ways, some progress towards bringing these policies closer to one another has been achieved. This is due to the application of common principles and concrete instruments, mainly the ecosystem approach and maritime spatial planning. The ecosystem approach has indeed started to filter into sectoral policy-making, in particular with regards to fisheries, the environment and—to a lesser extent—regional development. Integrated maritime spatial planning is a slow process but, induced through EU legislation (Directive 2014/89/EU), it makes a difference throughout European seas. In contrast to these examples, the Arctic policy is not likely to lead to that type of integration. Creating a single policy out of the EU’s various Arctic-relevant sectors seems hardly feasible. This does not seem to be the intention of EU policymakers. As a matter of fact, in the 2016 policy update, the Commission and High Representative no longer talk about common Arctic policy objectives (which would guide action in all components of Arctic policy). These are now called – appropriately – “priority areas”; basically, aspects of EU presence in the Arctic:

- Climate change and safeguarding the Arctic environment

- Sustainable development in and around the Arctic

- International cooperation on Arctic issues

Integrated into sectoral policies: mainstreaming Arctic issues?

The second type of policy integration relates to cross-cutting issues feeding into various sectors of state or EU activity. The most obvious case for this is environmental and climate policy integration.5) Over the last decades – at least in the EU and many of its member states – environmental issues and climate policy targets have indeed found their way into such fields as transport, agriculture, fisheries, and regional development.

Could Arctic issues be integrated into wider sectoral policymaking in a similar fashion? Perhaps. The Joint Communication is not a definite statement of the EU’s policy towards the Arctic as it – in principle – is to inform other EU institutions on the position of the European Commission and High Representative. Nonetheless, it can be considered as an authoritative guidance to Commission services and it is likely to be endorsed by the Council. The text of the 2016 Communication states that “[t]his policy document should guide the EU’s actions for the coming years”. However, the marginal character of the EU’s Arctic policy in the broader European policy framework makes it rather challenging for Arctic-specific concerns to noticeably affect the course of EU policy-making in sectors such as environmental policy, agriculture, fisheries, transport or strategies for resource supply. Single cases exist where Arctic policy did indeed have some influence. From the dawn of the EU’s Arctic-focused policymaking, the Arctic started to pop-up in different contexts, from mineral resources and energy (e.g. Directive 2013/30/EU on safety of offshore oil and gas operations, referring to promotion of international standards for Arctic hydrocarbons extraction), to maritime traffic legislation (e.g. Directive 2009/17/EC on vessel traffic monitoring and information systems, referring to ice conditions). As another example, the Northern Periphery Programme became the Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme in 2014, albeit this was primarily a case of relabelling than actual change.

As a matter of fact, the 2016 policy statement provides some possibilities for further integration of Arctic issues. One example is the option of including protecting the Central Arctic Ocean into the EU’s position in the currently commencing UN negotiations on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction or the high seas. Another example is a possible – although difficult to implement—adjustment in the EU’s definition of key transport networks to support transport connections on the Europe’s North-South axis have been assessed as underdeveloped. Moreover, the proposed forum and network for national and regional authorities from European Arctic and managing authorities of EU programs (see Part II), which shall support EU Arctic funding cooperation—could lead to adjustments in the future set-up of EU structural funding. However, examples of proposals to mainstream Arctic issues into broader, pan-EU decision-making processes are few and uncertain as regards implementation.

Integrated “laundry list”: Building on the EU’s general policies?

The third way to understand “integrated policy” concerns the policy itself that could eventually be integrated into existing frameworks, policies and activities. EU policymakers sometimes seem to apply this line of thinking, as shown in their analysis of the added value of macro-regional strategies.6) Simply, an integrated policy would mean here one that builds on and takes account of principles and objectives of general sectoral policies (like climate, environment, transport or regional development).

To some extent, this is exactly what the new Arctic Communication does. We learn that EU activities in the Arctic will be in line with EU climate mitigation and adaptation policies or the EU Maritime Security Strategy from 2014. The expected evolution of the EU’s overall cohesion policy towards greater focus on investment loans might lead to a decrease of funding available for the European Arctic regions through regional and cross-border programmes,7) showing how dependent the EU’s actions in the Arctic are on its overall policy frameworks.

The result is that the Communication – similarly to its predecessor – remains a set of “statements of fact rather than commitments to action, which appear to be in great part a continuation or intensification of existing activities at EU, bilateral or multilateral level”, as Airoldi8) concluded at the previous 2012 Joint Communication. The 2016 document largely constitutes a list numerous activities, studies, and projects that have already taken place and provides fairly few examples of actions yet to be taken: from existing satellite technologies, through ongoing operation of the EU-Polarnet (formulating the European Polar Research Programme), to very specific projects to be continued, like the development of multi-resolution maps of the Arctic seabed. Proposals for future activities are few. The Communication is certainly not an action plan.

The EU Arctic policy as “anything that gets to be implemented”

The so-called “EU Arctic policy” is in fact a policy on “anything that gets to be implemented”. Eventually, we should perhaps accept it as such – as an overview of the EU’s Arctic-relevant policies and actions – and thus, limit our expectations boosted by the EC/HR’s claim of establishing an “integrated policy”, a policy that is something more than just a sum of its parts.

The primary role of the Communication is not to streamline EU Arctic policies and actions but to communicate the scope of the EU’s presence in the region, to show that the Union has an appropriate understanding of the situation in the region and to state overall principles that the EU commits to follow in its diverse Arctic activities. The key audiences are the Arctic states, EU member states, and to some extent the general public. Neumann9) famously asked “why diplomats never produce anything new”, suggesting that diplomatic statements are about diplomats communicating with one another with the assumption that all relevant issues need to be mentioned, with one common voice and emphasis upheld. While the EU Arctic communication is not exactly an external relations statement – it cuts across external and internal affairs – it also has to incorporate all possible Arctic-relevant issues. That is because not mentioning something would become a statement in itself.

As a result, the Communication’s authors had little choice but to present an ever longer list of Arctic-relevant aspects of EU activity: research, resources, sustainable development, dialogue with Indigenous Peoples, Arctic Council as a primary forum for circumpolar cooperation, UNCLOS as a key legal framework for Arctic Ocean, etc. Considering the number of aspects brought under the umbrella of the EU Arctic policy, limiting many aspects to being just mentioned – resulting in the document looking like a long “laundry list”10) – is perhaps a blessing as more substance would turn the Communication into a 200-page-long report.

Limits to the EU’s influence

The lack of policy integration is coupled with the Commission’s and the EEAS’ understanding of the limits on the EU’s ability to influence developments that are important in and for the Arctic. The EU can only “encourage” its international partners to speedily ratify the Minamata Convention on Mercury and the Ballast Water Convention, both yet to enter into force. Moreover, it can only encourage Arctic states to effectively implement the Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants (although the dialogue with China would be rather important from an Arctic perspective), where the EU itself has done a relatively good job. What is missing in this list of encouragements is any call for limiting the use of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic, a measure that has not found its way into the mandatory Polar Code. This is strongly opposed by Russia, as Moscow is concerned about the costs of operating its domestic Arctic destinational shipping. Despite declaring a “duty to protect the Arctic environment” and being a “global leader in science”—two essential components that aim to highlight the Union’s Arctic credibility—the EU is a secondary participant to many Arctic institutions and attempts to tread carefully as to not offend Arctic states. Unfortunately, too often the fundamental question as to how the EU could encourage its partners or facilitate developments is unanswered in the 2016 Joint Communication.

Summary

In conclusion, it is difficult to imagine that EU officials who specifically deal with Arctic issues can formulate a strong cross-cutting framework, let alone make a significant impact on larger processes taking place in the EU. Considering that an integrated Arctic policy is a rather unlikely creature, perhaps it is time for the EU to issue Arctic statements on more specific issues. What is the role of the Arctic region in the Union’s implementation of the Paris Agreement? What are the implications for the EU’s Arctic-relevant activities stemming from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015, relevant in principle for the whole world and mentioned in the new Communication? Is it possible to have a policy statement focused on the European Arctic – perhaps as an outcome of the European Arctic Stakeholder Forum process – as a part of the new framework for the regional policy in the next EU budgeting period 2021-2027?

Although the EU’s Arctic policy will to a great extent remain a mere listing of EU Arctic-relevant activities, it certainly does not mean that it is irrelevant. It is important as a way of communicating EU Arctic activities and general principles the EU and its institutions acknowledge. The process of drafting a communication also makes EU officials reflect on the EU’s overall place in the region.11) Eventually, the new document does propose some more concrete outputs regarding European Arctic affairs and possibilities for future coordination within the EU institutions, as well as coordination of various sources of EU Arctic funding (see Part II).

References